We sat down with Hanan Sayed Worrell to hear how arriving in Abu Dhabi in the early 1990s as a civil engineer led to three decades shaping the city's most consequential projects — from the airport and Al Ain Wildlife Park to the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and NYU Abu Dhabi.

Today, as Head of Placemaking at MiZa, she is helping shape Mina Zayed into a creative, entrepreneurial neighbourhood as part of a broader government vision. Hanan shares her perspective on the relationship between hard and soft infrastructure, why food and memory matter as much as buildings do, and how Abu Dhabi can move from a global crossroad to a cultural compass.

You've helped shape Abu Dhabi through major projects — from the Guggenheim to NYU Abu Dhabi, Al Ain Wildlife Park to Expo 2020 Dubai and your writing. What's the connecting thread?

My path in Abu Dhabi wasn’t something I ever master-planned. I arrived in the early 1990s with a master's degree in civil engineering, a consulting career in New York, and two young toddlers in tow — expecting a short stay while my husband worked on an oilfield project in the desert.

Opportunities for women in engineering were scarce then, but eventually I found my way into my first project here: building the new airport for the Presidential Flight. That opened my eyes to how the discipline of engineering — problem-solving, clarity, teamwork, and coordination — could apply to any field when guided by purpose.

Since then, my projects have ranged from airports and refineries to museums, universities, conservation parks, and even a zoo. When people ask what I actually do, I often laugh and say, “Everything from A to Z — airports to zoos.” I've also worked on projects like Expo 2020 Dubai and contributed to Expo Osaka — both exercises in storytelling about nations and their aspirations. These expositions sit at the intersection of hard and soft infrastructure, translating a country's vision into immersive experiences that visitors can inhabit and understand.

But the truth is, the thread between them is consistent. Each project begins with a vision — a civic or cultural idea — and the task is to translate that idea into a built environment that people can inhabit and feel connected to.

What ties them together is the act of translation: between disciplines, between cultures, between imagination and reality. Over time, I’ve learned that buildings and institutions are really vessels for stories — about who we are, what we value, and the future we hope to build.

Table Tales celebrates how cities grow through shared experiences, not just buildings. How do food, memory and community shape Abu Dhabi's identity today?

Since Table Tales was first published seven years ago, Abu Dhabi has continued to evolve at remarkable speed—embracing knowledge industries, digital transformation, space exploration, and innovation across every sector. Regulations have made it easier to build businesses and lives here, attracting a new generation of entrepreneurs and creatives from major global cities. With them comes a different level of sophistication and curiosity—reflected in restaurants, design, and the ways people gather.

But as the city grows, the question of community becomes even more essential. The Abu Dhabi of the 1990s felt like one big village; today it’s a constellation of neighbourhoods spread across islands. The challenge — and the opportunity — lies in sustaining that spirit of everyday connection through shared meals, local markets, creative spaces, and friendships that cross cultures.

Food, in that sense, remains the most democratic form of placemaking. It reminds us that identity is not static — it’s continually simmering, taking on new flavours while remaining profoundly human. As archaeologists remind us, we’re the only species that shares food with strangers — people beyond our own family or tribe. That simple act of hospitality, whether offered as a feast or a cup of coffee, is what makes us civilised.

Abu Dhabi’s story is being written at countless tables: in family homes, in cafés run by first-time entrepreneurs, in restaurants led by chefs who arrived as visitors and stayed to belong. Each table adds another ingredient to the city’s evolving recipe — one that tastes unmistakably of home.

You've shaped both the physical development of Abu Dhabi and its social fabric. How do those two layers influence each other?

I often think of cities as having two kinds of infrastructure: the hard and the soft. The hard is what we see: the buildings, the roads, the systems that connect us physically. The soft is what we feel: the culture, programmes, and relationships that give those structures meaning. Neither can thrive without the other.

Cities everywhere are linked by their physical infrastructure — roads, ports, airports, data cables — the veins and arteries that keep them alive. But what distinguishes one city from another is its culture: the way people live together, create, and express a shared sense of belonging. Infrastructure connects cities; culture distinguishes them.

When developing institutions like the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi or NYU Abu Dhabi, understanding the soft infrastructure — the community, the context, the cultural nuances — was as critical as designing the physical form. The architecture had to anticipate the life that would unfold inside it: the students, visitors, artists, and residents who would give it purpose.

In a way, these projects mirror the city itself. They advance knowledge, culture, and dialogue, helping people deepen their understanding of one another. Over time, that’s how cities evolve — not only through what they build, but through what they nurture.

Your current work in placemaking at MiZa brings together art, culture, and urbanism. What does placemaking mean to you in the context of the UAE’s rapid growth?

For me, placemaking is about shaping environments where community, creativity, and everyday life intersect — places that feel lived in, not just designed. At MiZa, we’ve been reimagining Mina Zayed, Abu Dhabi’s original port, as a creative and entrepreneurial neighbourhood that connects diverse thinkers, makers, and doers. It’s an exercise in balancing heritage with future possibility.

In a city that changes as quickly as Abu Dhabi, placemaking becomes a way to slow down — to listen, observe, and ask what a place wants to be rather than what we want to impose on it. The work is part urban strategy, part cultural choreography. It’s about creating public realms and shared experiences that invite collaboration, belonging, and pride of place.

At its best, placemaking is not a finished product, but an ongoing conversation — between past and future, and between city and citizen. It’s how we make growth feel human.

You’ve witnessed the transformation of Abu Dhabi from an intimate community to a global city. What do you hope the next chapter of its cultural story will look like?

I hope the next chapter builds on confidence — a confidence rooted in who we are. The past two decades were about inviting the best of the world to collaborate here, to jump-start sectors like culture, education, and design. That foundation has been transformative. But I think the coming years are about authorship — about voices, ideas, and enterprises that originate here and speak outward.

As Abu Dhabi continues to grow, I hope it doesn’t lose the generosity and humility that defined its earlier years. I’d love to see a distinctly Abu Dhabi way of living and creating take shape — one that draws on global influences yet remains deeply grounded in local values of hospitality, community, and care for the land. The city has always been a crossroads; now it has the chance to become a cultural compass.

On a personal note — where in Abu Dhabi do you feel most connected to the city’s spirit?

The Corniche still feels like the city’s heart to me. It was where we first lived when we arrived in 1993, and it remains a place of memory and continuity. Over the years, we’ve jogged, biked, picnicked, celebrated birthdays and national days, watched fireworks, and seen the skyline rise behind us. It’s welcoming and accessible — a place where everyone belongs, from every walk of life.

Even as the city has expanded beyond the main island, the Corniche remains its north star. It’s verdant, open, and ever-changing — a living palimpsest of the city’s growth. On my daily walks, I pass people from a dozen different nationalities, each moving at their own rhythm, yet somehow part of the same flow.

That, to me, is Abu Dhabi: diverse, grounded, and always in motion.

About Hanan Sayed Worrell

Hanan Sayed Worrell is a cultural strategist and placemaker whose work bridges the built environment, culture and community. A civil engineer by training, she has spent over three decades shaping projects that connect people to place — from the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and NYU Abu Dhabi to Al Ain Wildlife Park, Sheikh Zayed International Airport, Expo 2020 Dubai, and beyond.

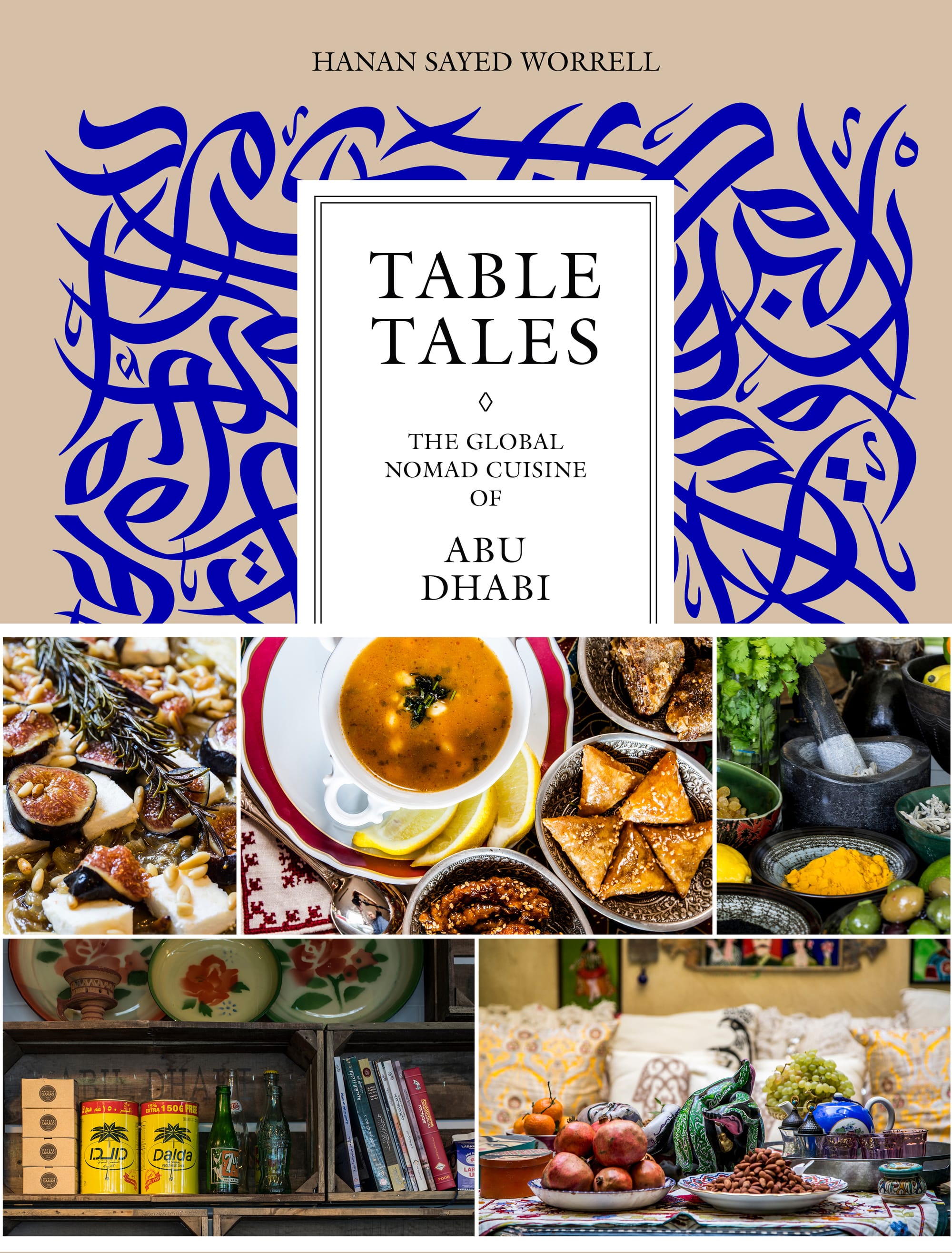

She is also the author of Table Tales, a celebrated book that explores how food, memory, and hospitality create belonging in a diverse city. Since arriving in the UAE in the early 1990s with her husband, Steve, and their two young children, Tala and Badr, Hanan has become a leading voice on the relationship between culture and the built environment in rapidly transforming cities.